Why Ancient Igbo Dibias Did Not Eat Oha Soup

Food, in many indigenous cultures, is never just food. It is memory, symbolism, and theology served in a bowl. Among Igbos, meals, like most things in Igbo worldview, typically sits at the crossroads of the physical and the spiritual, carrying meanings that go far beyond taste or nourishment.

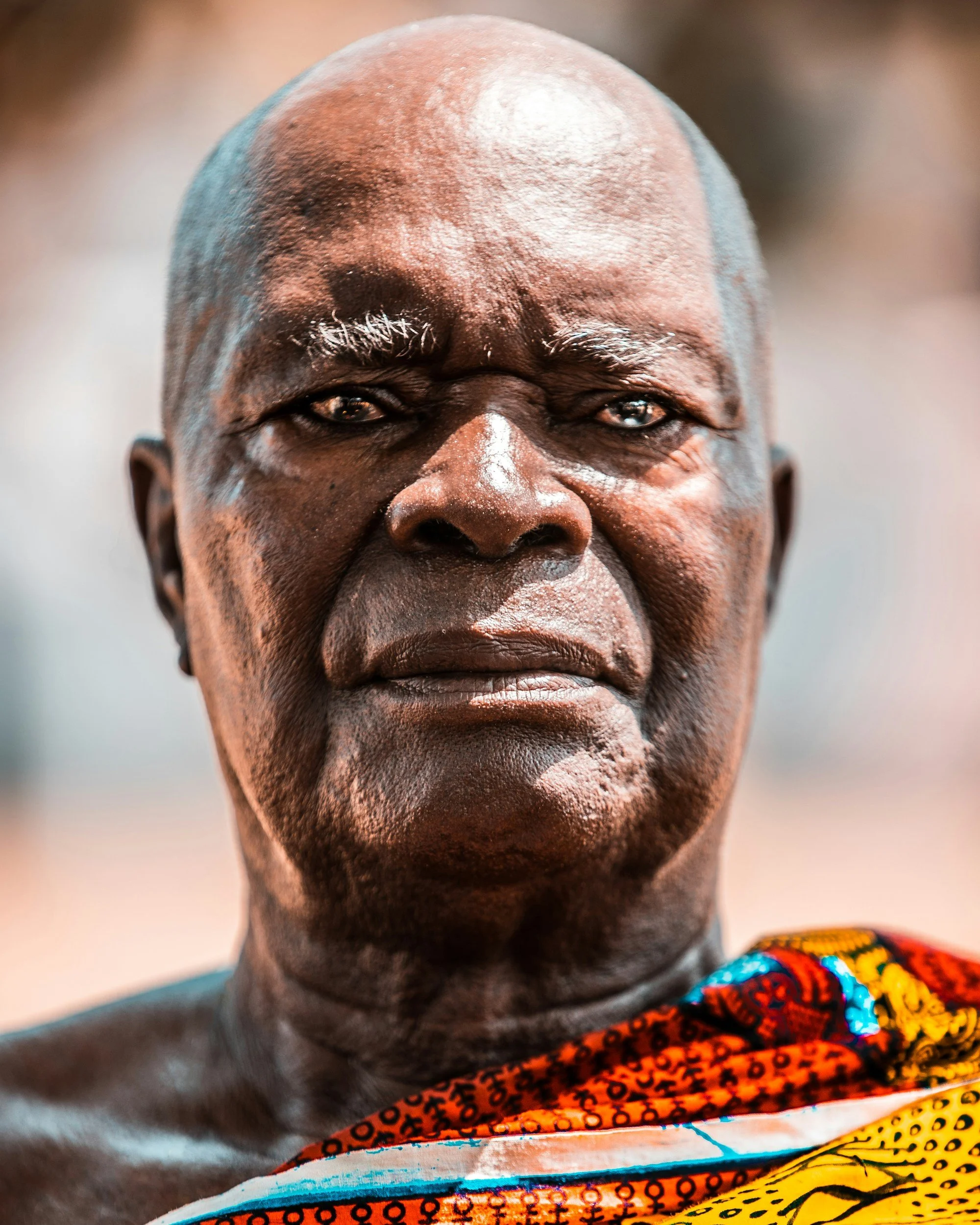

One of the most intriguing examples of this depth is the ancient traditional practice that ancient Igbo dibias (priests, healers, and mystics) did not eat Ofe Oha (or Ofe Ora). At first glance, this seems puzzling. Oha soup is beloved, nutritious, and deeply cultural. Why would those most grounded in Igbo spirituality avoid it?

The answer has less to do with taboo, and more to do with reverence.

In Igbo mysticism, Oha/Ora is not just a tree. It is Ora Chukwu, a plant sacred to the Supreme Being, (Nne)Chukwu, the universal Chi and ultimate source of existence. The leaves used in Oha soup were understood as belonging symbolically, and spiritually, to Chukwu as the Supreme Source and Creator of All Things. For the initiated, to consume them casually would be to collapse an important boundary between the human and the divine.

Ancient Igbo cosmology was built on balance and hierarchy. While the spiritual and physical worlds interacted constantly, they were not meant to be treated as equal. Certain things were set apart; not because they were forbidden in a moral sense, but because they were consecrated.

The Oha tree occupied this sacred category. It represented vitality, continuity, and divine presence of Chi-Ukwu itself woven into nature. Eating from it, for a dibia whose life was already devoted to mediating between worlds, would have been an act of overfamiliarity with the Supreme Being.

This restraint speaks volumes about the spiritual discipline of the dibia. Contrary to modern assumptions, power in Igbo spirituality was not about excess or entitlement. The more spiritually elevated a person was, the more careful they had to be. Dibias lived under stricter symbolic laws than ordinary people because their role demanded clarity, humility, and alignment. Abstaining from Oha soup was a way of maintaining spiritual attunement and reverence, an acknowledgment and a constant reminder for the Igbo mystic that not everything sacred should be consumed, even if it is accessible.

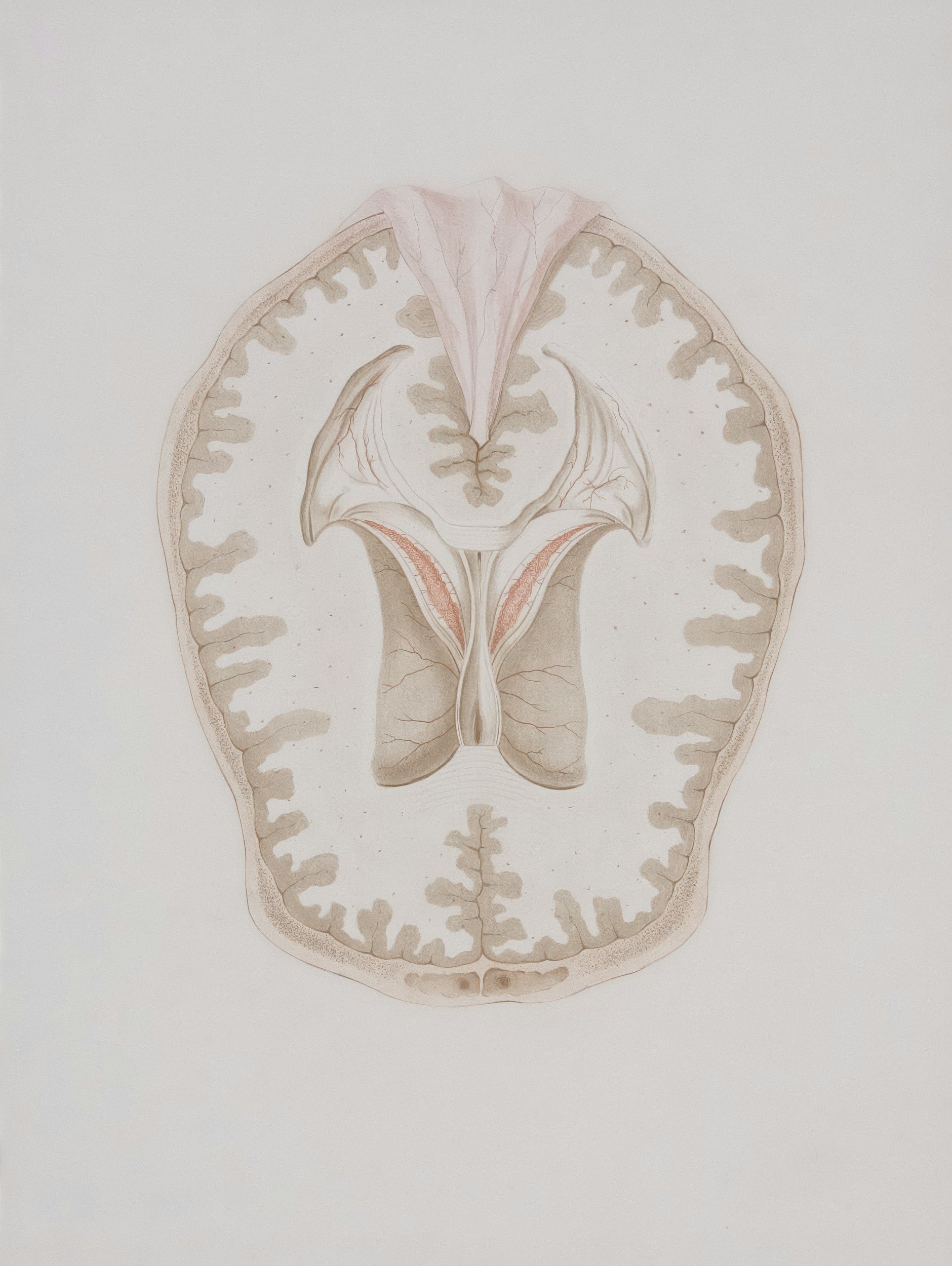

There is also a deeper metaphysical logic at play. The dibia was seen as a vessel through which spiritual forces flowed. To ingest something directly associated with (Nne)Chukwu risked spiritual imbalance. In Igbo thought, too much proximity to raw divine essence could destabilize a human being. Respect, therefore, required distance. The dibia affirmed the supremacy of Chukwu while recognizing human limitation by refusing Ofe Oha.

Interestingly, this practice also reveals how Igbo spirituality resisted spiritual arrogance. The dibia, despite possessing knowledge of herbs, incantations, and the unseen, did not place theirself above cosmic order. Instead, they modeled surrender to it. Their power came not from honoring the sacred in their lifestyle.

With time, colonial disruption and the rise of Christianity flattened many of these nuanced distinctions. Oha soup became purely culinary, stripped of its metaphysical weight. Today, it is eaten freely by all, including spiritual practitioners, mostly without awareness of its former sacred associations. Yet the old belief remains a quiet reminder of how deeply intentional Igbo spiritual life once was.

Ultimately, the reason ancient Igbo dibias did not eat Oha soup is not strange or irrational. It is immensely philosophical. It reflects a worldview that understood the universe as layered, ordered, and alive with meaning.

In choosing not to eat what was sacred to (Nne)Chukwu, the dibia affirmed a timeless truth, that reverence is sometimes best expressed not through possession, but through restraint.

Recommended Resources:

An Introduction to Nso (Personal & Communal Taboos) in Odinani | Odinani Mystery School

Ekwerem Agwu (Making Peace With Agwu and Accepting Your Spiritual Calling) | Odinani Mystery School

Join Odinani Mystery School for access to Exclusive in-depth teachings on ancient Igbo wisdom and mystical sciences!

Igbo writer, mystic and philosopher.