Who Is Responsible for Moral Behavior in Odinani?

When we speak of morality, especially in spiritual contexts, many traditions point upward to a Supreme Being who watches, judges, and punishes. In Christianity, it’s God. In Islam, it’s Allah. In many other belief systems, moral law is attributed to a singular divine lawgiver.

But in Odinani the picture is more intricate, more grounded, and deeply communal. While Chineke or Chukwu as the Supreme Creator occupies the highest metaphysical position, Chukwu is not the primary judge of daily human morality.

Instead, moral behavior in Odinani is primarily shaped, judged, and maintained by three distinct spiritual forces: Ala (the Earth goddess), the Ancestors, and a person’s Chi.

Let’s explore each of these powerful forces and what they teach us about responsibility, ethics, and the sacred art of living rightly.

1. Ala – The Moral Custodian of the Land

Ala (Ana/Ani) is the Earth goddess, and arguably the most active spiritual force in Igbo moral life. She is not only the deity of the physical earth but also the guardian of morality, justice, and community laws.

In Odinani, it is Ala who defines the boundaries of acceptable and unacceptable behavior. All acts of wrongdoing, especially those that disrupt harmony, defile the land, or violate the community's well-being, are considered abominations (nso Ala). These include murder, incest, theft, injustice, and other moral failings.

Because Igbo ancestors viewed the Earth itself as living, conscious, and sacred, violating its principles was not merely a social issue, it was also considered a spiritual desecration. And since every person lives and thrives on the land, Ala holds everyone accountable, not from a distant heaven, but from beneath one’s very feet.

Ala is also the one who receives the dead, further emphasizing her role in connecting the moral decisions of the living with the spiritual realities of the afterlife.

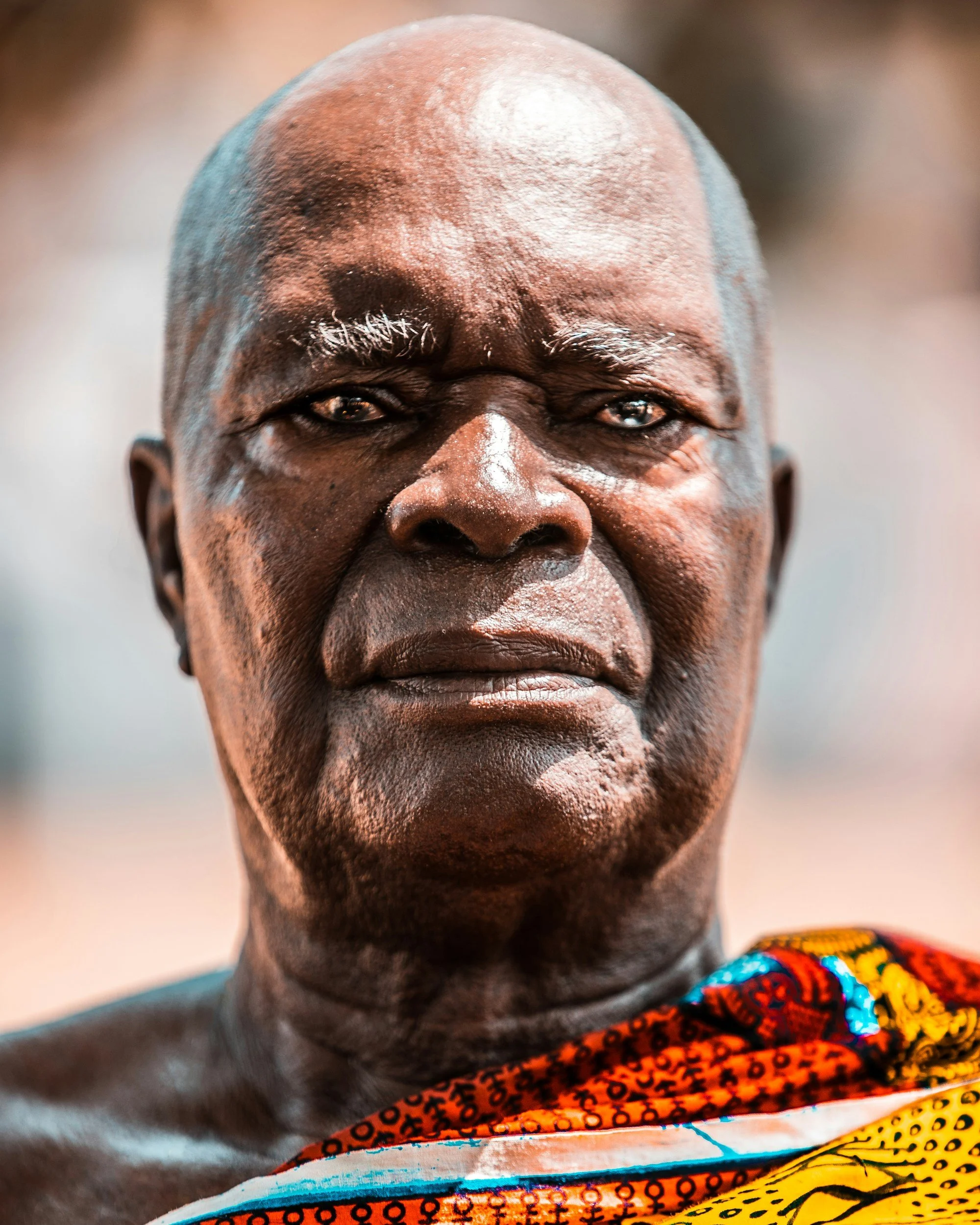

2. The Ancestors – The Eyes of the Community

The second moral authority in Odinani is Ndi Ichie (the ancestors), those who lived righteously, fulfilled their destinies, and were honored in death. These ancestors become spiritual guardians of the lineage, watching over the living and making sure that tradition, honor, and justice are preserved.

Ancestral spirits are active forces in family and community affairs. They reward righteous behavior and punish disobedience, disrespect, or deviation from communal values. In fact, to act immorally is not just a personal failing, but also seen as a disgrace to one’s lineage.

When someone behaves immorally, they’re are pictured to be “dragging” their own family’s name in the mud. This speaks to the deep belief that we are not isolated individuals, but extensions of those who came before us. Ancestors are therefore both judges and models of what moral living should look like.

3. Chi – The Personal Spiritual Witness

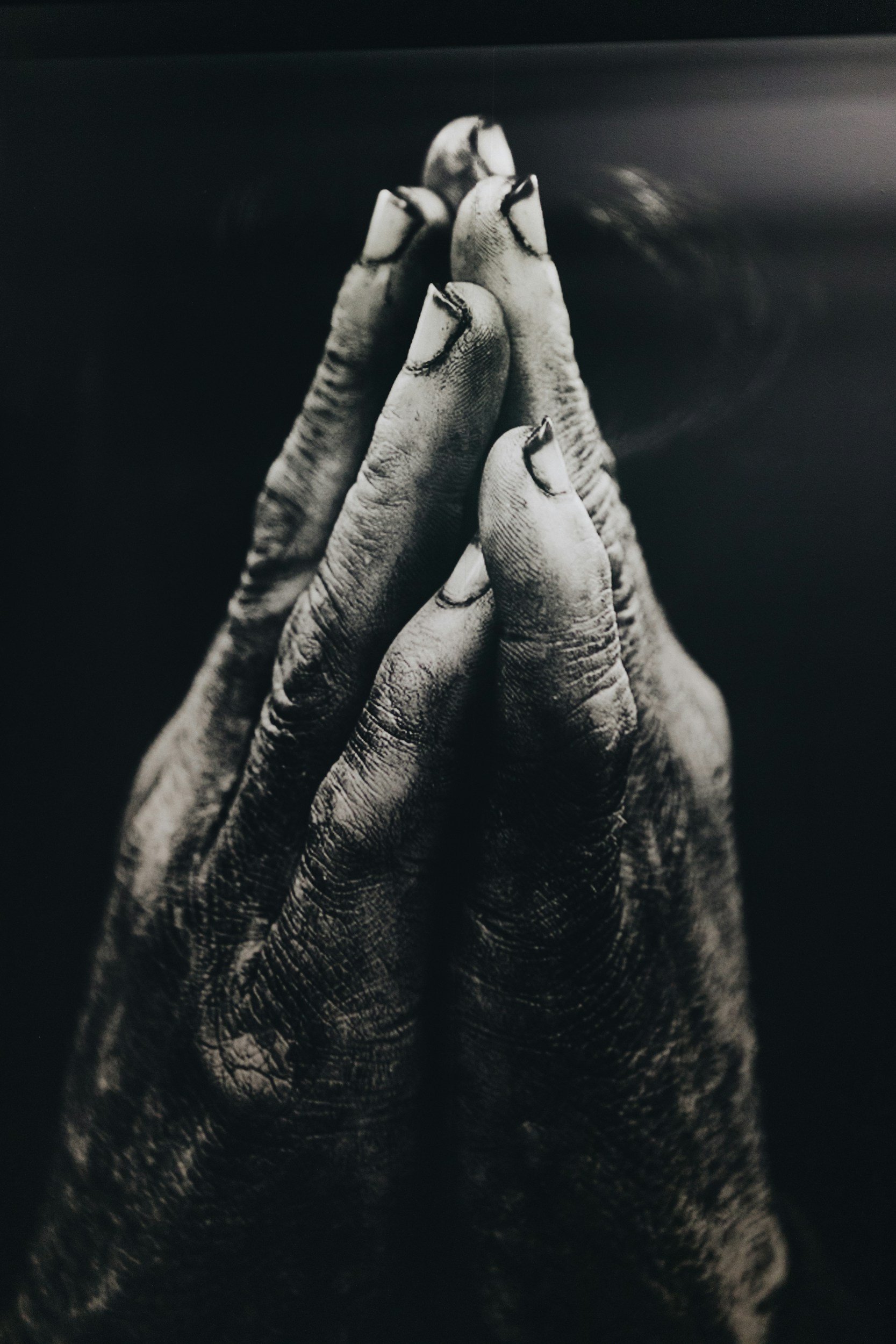

Perhaps the most fascinating element in Odinani’s moral framework is the role of Chi, which is in a sense one’s personal spiritual double or guardian assigned to each person at birth.

Your Chi is your destiny compass. It does not force your decisions, but it witnesses them. It guides, warns, inspires, and holds you accountable as the closest divine presence within you.

When a person strays from their path, betrays their calling, or lives out of alignment with truth, it is believed that their Chi turns its back on them, which is the worst thing that can happen to an Igbo person. This is a natural spiritual consequence of being out of integrity with your inner self.

To be morally upright in Odinani is therefore not just to obey external laws but to live in alignment with your personal destiny and the divine purpose encoded in your being.

So, Who Judges the Moral Life in Odinani?

The answer is not Chukwu or Chineke, the Supreme Creator. While revered, Chukwu is too transcendent to micromanage daily morality.

Instead, the responsibility falls on:

Ala – who governs communal ethics and the balance of the land.

The Ancestors – who guard the honor and continuity of the lineage.

One’s Chi – who ensures personal accountability and destiny alignment.

Together, these three form a spiritual triad that monitors, judges, and maintains morality in Igbo spiritual consciousness, not from a place of punishment, but from a deep commitment to balance, purpose, and communal harmony.

What This Means for Us Today

The philosophy behind moral responsibility in Odinani offers invaluable insights:

Morality is local – it is judged by the land you walk on, not some distant deity.

Morality is communal – your actions reflect on your ancestors and community.

Morality is personal – your Chi knows when you are living a lie.

This worldview encourages deep accountability, not just to laws or gods, but to the earth, your lineage, and your own soul.

So next time you ask, “Am I doing the right thing?” Listen to the earth. Honor your lineage. Consult your Chi. That is where the true judgment lies.